A red village. This is how Radinac – a village about a 15-minute drive away from the center of Smederevo – can be described in three words. The walls of houses, air conditioning units, antennas, lamp posts – everything that was once white is now a copper, dark red color. And not by the will of the inhabitants – the Železara Smederevo steel mill gets the “credit” for the village’s appearance.

Red rain is waste water released by the HBIS GROUP Serbia Iron & Steel company, better known as Železara. This rain has a negative impact on health, just like steel dust, as they call the shavings of heavy metals and ore released by the industrial complex around these parts, explains Vladimir Milić, 33, one of the few denizens of Radinac to speak publicly about this:

“The throat is sore, scratchy, there is some nausea in the stomach. When that red rain starts, we make sure not to be outside. We run, shut ourselves in our rooms. (…) It’s the same with steel dust – it’s impossible, it gets into the eyes, mouth, nose, ears. You have to walk down the street with your eyes closed.”

At the farmers’ market, he and his family do not buy locally grown fruit and vegetables, but rather only from distant villages.

“I wouldn’t recommend living in Radinac to anyone,” says Milić.

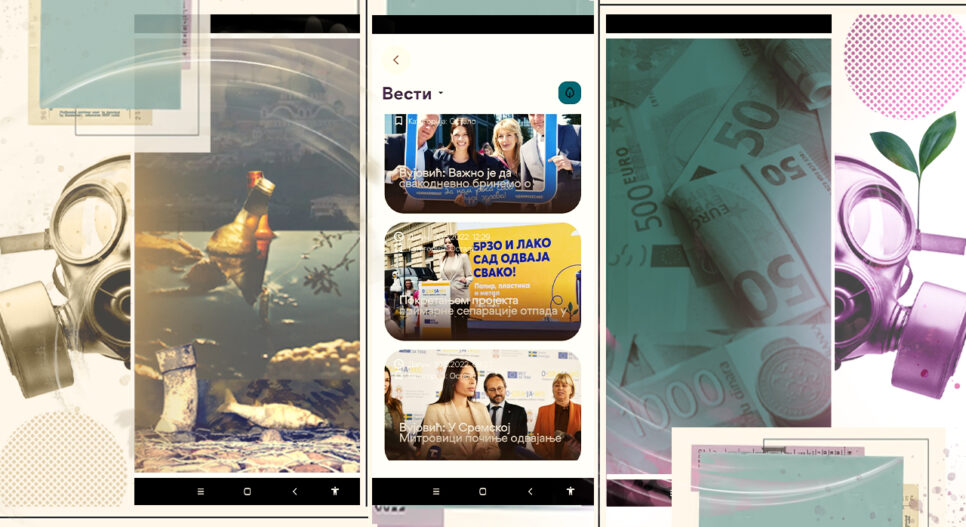

Gallery of photographs from Radinac; photo: CINS

The villagers see and feel the pollution, but do not know just how polluted the air they breathe every day is.

From 2015 to the end of 2017, Smederevo and nearby small towns and villages officially did not fall into any pollution category – the area was unrated, according to Serbian Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA). In 2015, two SEPA stations were operational and then just one, and so the category was not determined due to the small amount of data.

Since 2018 there has been a little more air quality control, thus Smederevo ended up on the list of most polluted places in the country, but without data from the station in Radinac, which did not operate that year. Only in late 2019 was this station launched, for 15 days, out of which pollution up to fourfold above permitted levels was registered during 11 days. PM10 particles were measured – a mix of dust, heavy metals and soot that enters the lungs directly and damages health. Monthly reports by the Pančevo Institute of Public Health for 2020 show that PM10 levels in the villages around Železara are still higher than permitted. The quality of air is monitored in the yard of Milić’s next door neighbor, but it is done for the factory, not the villagers.

An analysis conducted by the Center for Investigative Journalism of Serbia (CINS) shows that there have been problems in other towns and cities, too, over the past few years, because some stations did not monitor pollution for a sufficient number of days to draw any conclusions, while some did not measure certain types of pollution or were shut down. This is the case in, among other places, Belgrade, Beočin, Loznica, Čačak, Paraćin, Kruševac, Niš, as well as in Kosjerić which, like Smederevo, had been unrated until it found itself among the most polluted places.

From 2010, when the automatic system of measuring the concentration of pollutants was set up, to 2018 when annual data on the quality of air were last publicized (the report for 2019 has not been made public yet), the number of stations whose scope of monitoring met the criteria defined by regulations gradually decreased. In the last five years for which the data were unveiled, between 50% and 80% of the data from the stations (the number of which ranged from 33 to 39) is unusable, according to SEPA. Certain cities, such as Niš, were registered as unpolluted in 2018 just because the stations did not measure the concentration of the dominant pollutant in the country – PM particles – during the year.

That year the air in Serbia was rated as clean, whereas excessive pollution was attributed only to a few cities and towns.

Vladimir Đurđević, a professor at the Faculty of Physics in Belgrade, believes that the data obtained in this way “send a message that is not realistic.”

“The data clearly point out that the quality of air is disastrous. What is measured is reliable, but the amount of it is insufficient,” says Đurđević, adding that pollution would turn out to be higher if stations operated at full capacity:

“If we had 95% of data from all stations, received for all pollutants to be monitored, then one could not find a city in Serbia whose quality of air was better than category three. Therefore, they would all probably be in the worst category.”

The data analyzed by CINS back up this claim.

According to national regulations, most pollutants should be measured at least 90% of the time per year. In 2011 alone, after a more up-to-date system of monitoring on the hour was introduced, that scope was achieved for 94% of the data, which is the biggest success of air quality monitoring in the country, including the last report published.

For example, in the Zeleno Brdo quarter of Belgrade’s Zvezdara District, 134 days of excessive PM10 pollution were registered in 2011. That same year, a station in Niš showed excessive PM10 pollution for 167 days – which put Niš in the worst, third category. In 2018, there were no data for these particles from these stations because they had not performed monitoring for a sufficient amount of time.

From 2014 to the end of 2017, 39 stations provided between 22% and 30% of relevant data. The situation improved slightly in 2018 when less than half of the data from (then) 33 stations met the required scope of monitoring.

Due to a lack of such data, from 2013 up until the last report published SEPA drew conclusions on air pollution based on lower criteria, too, by using data from the stations that had more than 75% of valid data over the course of the year.

Former SEPA director Momčilo Živković, during whose term in office this system was established, disagree with this work method.

“As far as I am concerned, anything below 90% is not valid and should be discarded. That is not relevant data,” Živković told CINS.

SEPA did not respond to a request for an interview made on June 18, nor did it answer any of the questions we subsequently sent. Agency officials also did not submit data in line with the Law on Free Access to Information of Public Importance, under which CINS requested information on monitoring stations in the area of Smederevo, the money they invested in station maintenance, setup of new stations etc.

Due to discontinuous monitoring, according to Vladimir Đurđević, a quality analysis of what the sources of pollution are and how to solve that problem cannot be carried out.

Money for Reconstruction from Budget Instead of from Fund

Thirty-four stations are currently monitoring levels of sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), suspended particulate matter PM10 and PM2.5, ground-level ozone (O3), carbon monoxide (CO) and benzene (C6H6). Where measured, particulate matter is the main cause of all excessively polluted places in the country. Medical doctors warn that these particles may be the causes of diseases with a possible fatal outcome, may lead to bronchial asthma, chronic bronchitis and lung cancer. SO2 and NO2 cause respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, and harm children, the elderly and persons with chronic lung diseases the most.

The data from CINS’ analysis show that the air in Serbia has been dangerous to breathe for years now. Nonetheless, there has been no real picture of pollution in Serbia for years due to a lack of maintenance of state-owned monitoring stations – primarily because of a lack of money.

On several occasions, in its reports on air quality SEPA warned that there were “pronounced difficulties (in air monitoring) due to unresolved financing of the servicing and maintenance of equipment in the state network.”

Former SEPA director Momčilo Živković explains in an interview with CINS that the Environmental Protection Fund had been key to maintaining the monitoring system until it was shut down in September 2012:

“When they terminated the Fund, they practically cut off the branch that air quality monitoring system had been sitting on.”

Problems arose immediately after the Fund’s shutdown, shows a memo Živković sent to CINS. He addressed then minister of energy, development and environmental protection Zorana Mihajlović over debts incurred through previously arranged deals for maintaining monitoring stations, which were to be paid through the Fund, as well as over difficulties in current monitoring and concern that they would not be able to put together a report for 2012.

Since 2017, funds have been earmarked in the Serbian budget in the amount between 76 and 79 million dinars for air quality monitoring, while the purpose of the money for 2020 has been merged with water and sediment monitoring and totals roughly 120 million dinars. Through public procurement procedures, SEPA spent the bulk of the money for monitoring on spare parts and other equipment. However, the documentation does not show to which stations the equipment has been delivered. Aside from not enabling an interview with a SEPA representative, the Agency did not hand CINS data on specific investments in the stations – by SEPA or other state institutions.

Local network of stations assists in monitoring

In its reports on air quality, SEPA uses data from its own, state network, but also from local networks of stations which are most often managed by public health institutes. Thus it included 14 local stations in the data for 2018 – three each in Belgrade and Pančevo and one each in Kraljevo, Kikinda, Sombor, Obedska Bara, Sremska Mitrovica, Subotica, Novi Sad and Užice.

However, these stations also have a problem with monitoring. For example, eight out of 14 stations measure PM10 concentration, but not to an extent sufficient for adding that data to air quality rating.

Locally obtained information on SO2 and NO2 gases is rarely included in the report because the way in which a local network measures that concentration is not always comparable to SEPA data. It is a matter of different methods, explains former head of the department for air monitoring at SEPA, Tihomir Popović, and adds that those methods do not always align except where PM monitoring is concerned.

The stations’ functionality partially improved in 2018, as they were serviced and some spare parts were procured in 2017, reads the SEPA report.

The scope of monitoring was bigger that year, however, civil society organizations rallied around Coalition 27 in a report on the state of the environment say that, albeit enhanced, the data on the quality of air remain insufficient.

Ognjan Pantić of the Belgrade Open School is not happy with the rate of data publication, which cannot be followed live on the SEPA website, because people cannot react at the time of pollution:

“People learn in August 2019 what kind of air they breathed in 2018. (…) The only information they have until then is on (SEPA’s) website of automatic monitoring stations, where the quality of air at that moment is rated as excellent.”

Among those stations is the one in Radinac.

While waiting for the next Agency report, Pantić believes that SEPA is trying to do as much as it can with the means at its disposal, but adds that there is room for improvement in that area.

Besides funds for network maintenance, new stations need to be opened, too, explains Pantić. He mentions, as a positive example, the stations in Belgrade’s Vračar District and in Novi Pazar. PM10 monitoring in Novi Pazar began in February, with more days of excessive pollution registered by the end of May than what is permitted in a whole year.

What do you think