In late January 2018, journalist Tamara Skrozza received a text message from a female colleague: “Taša, what in God’s name is this?” Skrozza immediately guessed what it was about, turned on the TV and tuned into Pink TV. She recalls how she started shaking, because a feature was being run on the news about her and the Centre for Research, Transparency and Accountability (CRTA), where she is a steering committee member, and Pink was accusing them of working against the government. At first she didn’t feel afraid for herself, but rather for her child and mother.

“At that moment I didn’t think it was a danger to my life, rather I remembered that my child was in kindergarten and that some parent might see that news feature and that a fuss would be made at the kindergarten about whom their child was in kindergarten with, that those were traitors and mercenaries,” Skrozza told the Center for Investigative Journalism of Serbia (CINS) journalists.

On the news, Pink broadcast Skrozza’s statements from a journalists’ protest rally in 2015 and from an appearance on a satirical TV show broadcast earlier in 2018, taking them out of context and editing them in such a way that it seemed like she was calling Vučić a fool, faggot and pig-headed.

The reason for the attack on Skrozza was a report by CRTA which showed that ahead of the calling of the 2018 election of members of the Belgrade city administration the media favored the authorities rather than the opposition. Skrozza took part in presenting the report on January 23, and just a day later Pink launched its campaign against them.

The television aired the feature, but not CRTA’s press release on that occasion. Then, a few days later, it released a response to the press release with identical footage of Tamara Skrozza.

Although journalists’ associations and a portion of the public have for years been complaining about Pink’s unprofessional reporting and discrediting of the government’s critics, there was largely no reaction from the Regulatory Authority of Electronic Media (REM).

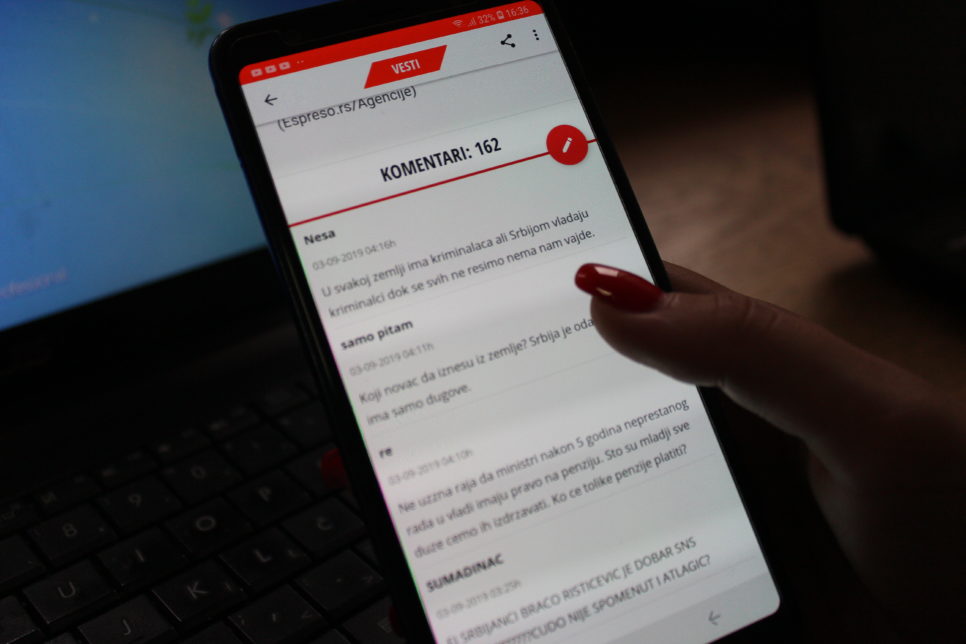

For that not to happen again, CRTA and the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia (IJAS) launched a campaign dubbed Wake REM Up, in which several hundred citizens in the first two months submitted reports to the institution asking to punish Pink for its reporting. REM remained silent.

In May, two months after the election, the citizens who had filed the objections received a reply in their e-mail inbox, which concluded – there is no reason to launch a procedure.

That was the REM Council’s decision, despite a different conclusion by their expert service.

The regulatory body’s Supervision and Analysis Service monitors media broadcasts, after which it sends a report to the Council for review. The CINS journalists had access to the reports pertaining to the objections filed due to the reporting on Tamara Skrozza and CRTA. They state that Pink violated three provisions of REM’s rulebook on human rights protection in the area of providing media services. This, along with the other rulebooks made by REM, gives a detailed definition of the media’s legal obligations pertaining to professional reporting, thus the violation of certain provisions may in fact also be interpreted as a violation of the Law on Electronic Media.

At Pink’s proposal, REM bundled up some 250 complaints against the television. In the report, the Service concluded that Pink had deliberately shortened Skrozza’s statements on Vučić, so that their context would not be understandable, in a bid to depict her as biased. It also says that the television denied Skrozza and CRTA the right to present their side, put parts of the organization’s press release into an ironic and demeaning context and did not clearly separate facts from opinions and comments. A similar violation was noted in the second report on the case, which the Council analyzed separately and which CINS also had access to.

Wake REM Up – the Sequel

In February 2019, at the height of the One Out of the Five Million civil protests against the regime of Aleksandar Vučić, the media reported on the possibility of a snap general election.

The Serbian Progressive Party then shot a video in which actors playing the roles of Dragan Đilas and Vuk Jeremić took money for the protests from a tycoon, and the video was broadcast by Happy and Prva TV.

Due to the fact that a political spot was aired outside of an election campaign, CRTA revived the Wake REM Up campaign. The regulatory body’s Council as early as the following day – February 6 – dismissed some 750 citizens’ complaints as unfounded. The appeal made by CRTA, for the parliamentary Committee on Culture and Information to review REM’s work, was rejected.

The REM Council reviewed these reports at four sessions and decided not to launch a procedure against Pink according to minutes from the sessions. For some complaints, broadcasters were allowed to state their opinion on the Service’s report, thus at the next session the Council decided against launching the procedure.

It is not clear from the minutes what made the Council members decide contrary to the violations registered by the Service. REM did not respond to CINS’ requests for access to information, specifically recordings of the sessions and all the decisions adopted in relation to this case, or to a request for an interview and the questions submitted.

Zoran Gavrilović of the Bureau for Social Research (BIRODI), an organization that has been following REM’s work for years, says that this is a model that is applied in other independent bodies, too. The profession does its job, but the problem arises among those who make the decisions – and who were chosen according to political party criteria.

“This is about a link between politics and televisions, and REM is just the connecting point,” said Gavrilović.

If You Don’t Like It, Change the Channel

The REM Service reports also point out other violations committed by televisions ahead of the 2018 election. At that time Pink aired negative reports on Dragan Đilas, the main opposition candidate for Belgrade mayor, where it was joined by the current candidate for the fifth free-to-air license, the Belgrade-based Studio B television.

Citizens reported to REM the controversial news aired by the television in February that year, which contained negative reports on the opposition leaders Dragan Đilas, Vuk Jeremić and Vesna Rakić Vodinelić, as well as a show called The Belgrade Panorama from the same month, in which the REM service noticed extremely positive reports on the authorities and negative ones on the opposition. In both cases a report was made, with the conclusion that Studio B did not clearly label the election campaign program, nor did it clearly separate opinions and comments from the facts, while on The Belgrade Panorama it did not allow all sides to be heard.

In both cases the televisions violated the rulebook on human rights and the rulebook on the obligations of media service providers during election campaigns, reads the expert service report.

Ivana Vučićević, the Studio B editor-in-chief, in her reply to REM said, among other things, that those who had submitted the report against the broadcaster were free to change the channel if they did not like the content. Vučićević also said that the complaints constituted interference with the Studio B editorial policy.

Studio B was not punished in any of the cases.

Similar violations did not lead to punishment of Pink either, which in late January 2018 reported that Đilas was making election campaign promises even though during the four years as a representative he had only come to one session, to verify his mandate.

According to the conclusions of the REM Service, which the CINS journalists had access to, it was an anti-campaign in which Pink did not separate opinions and comments from the facts, and denied Đilas the right to have his side heard. The program was not clearly labeled as part of the election campaign, either.

Verbal confrontation between the opposition and REM Council member Olivera Zekić, outside the regulatory body’s headquarters in October 2018; photo: printscreen N1 TV

The same as in Skrozza’s case, the controversial report on Đilas was the subject of a Council session almost three months after the election. The session was attended by Goran Gmitrić, the editor-in-chief of Pink’s news section, and the regulatory body’s decision reads that the television made a statement on the Service report. The epilogue came later, when the Council unanimously decided not to punish Pink.

Even after several calls, the CINS journalists did not get any comments from Gmitrić and Ivana Vučićević.

Gordana Suša, who was a member of REM during the rule of the Democratic Party and then the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), i.e. from 2010 to March 2016, says that reacting several months after an election was not regular practice.

“That is a scandal. In my time there were two elections. We held sessions day and night.”

How Did It Come to This

The documentation CINS got access to also contains three cases in which REM reacted to violations committed by Pink TV and one where it reacted to reporting by Studio B.

Veljković: REM Is Tiny Service of Serbian Progressive Party

The REM Council recently annulled its rulebook on the obligations of media service providers during election campaigns – a document that bound the media to treat the authorities and the opposition objectively and equally. REM Council member Goran Peković talked about that in an interview with the Insajder website in mid-March.

“I don’t know why that is a problem. We will not have an election soon. Our lawyers will draw up a new rulebook. Maybe work on that has already begun,” said Peković.

For almost two years the Council has been incomplete, six out of nine members attend sessions. Members from the civil sector and the university still have not been appointed, and attempts to appoint them have so far been accompanied by disagreements, and even a boycott by a group of civil society organizations due to, as the media reported, abuse and political pressure.

The notion that REM is not independent is shared by Slobodan Veljković, specifically since the session at which the Council did not punish anyone for broadcasting the SNS birthday live:

“In my opinion, that is the key moment when REM lost the independence it had been building in some way and which had been diminishing, and then it became a tiny little service of the Serbian Progressive Party.”

In early February 2018 Pink during its news program went live to a SNS rally in Belgrade’s Železnik quarter and directly aired a 24-minute speech by Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić. A month and a half after the election, REM sent a written warning to Pink about the obligation of labeling election campaign content.

A former member of the REM Council, Slobodan Veljković, in an interview with the journalists described this measure as “educational.”

The former REM Council members point out that in the past the regulatory body punished televisions during election campaigns, and offer the example of Studio B whose program the Council interrupted for violating the election silence ahead of the 2012 general election.

“Broadcasters addressed us, to send us a spot and get an opinion on whether that might violate the law. And we watched it, assessed it, allowed and even banned some,” Suša explained.

According to Veljković, a change could be felt already at the end of 2013 and the beginning of 2014, when the SNS started taking over the leading position in the government. One of the sessions he finds memorable is the one after the seventh birthday of the SNS – which was aired by Pink, Happy and Studio B. It was custom for the Council members to gather before the session and agree on important decisions beforehand. It was decided then, as he puts it, that televisions would be punished for airing the convention, but he later got a surprise at the session when the majority of the members voted against the decision.

“We broke our backs at the session. The lawyers who sided with me also broke their backs. After that I gave up on it all,” says Veljković.

The story was produced within the project supported by the ‘Freedom of Expression and Public Informing’ Programme of the Open Society Foundation Serbia.

From November 2018 to September 2019 the work of CINS is supported by Sweden, within the Belgrade Open School program “Civil Society as a Force for a Change in the Serbia’s EU Accession Process.”

What do you think